Can you put a number on how well a food balances human health and environmental impact? To answer this question, Mérieux NutriSciences | Blonk has been working for several years with companies, non-profits, and public organizations on applied research at the intersection of nutrition and sustainability. Building on this experience, we recently published a peer-reviewed scientific paper that lays out the methodology behind the Sustainable Nutrition Balance (SNB) score.

The SNB framework looks at the ‘whole picture’: it shows how a specific food, when considered as part of a complete diet, helps (or hurts) the balance between human health and the health of the planet.

Sustainable Nutrition Balance: How does it work?

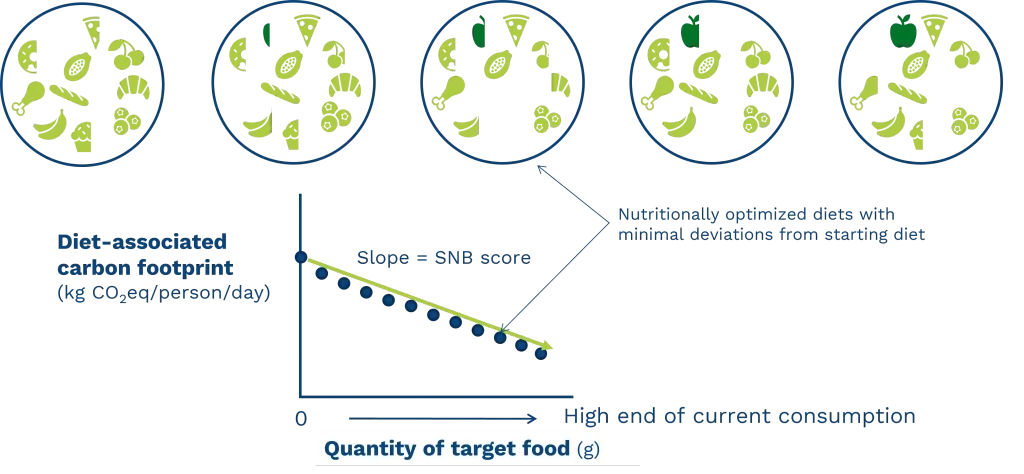

The process starts with an average diet that reflects what people currently eat. For each target food product in the diet, take apple as an example, the intake is increased step by step, from 0 g/d to a realistically large amount per day based on current consumption. For each fixed intake level, the diet is optimized to meet all nutrient requirements while maintaining the same energy content and minimizing changes from starting diet. This results in a series of nutritionally complete diets with equal energy content, each containing a different quantity of apples and corresponding environmental outputs (see Figure 1). After all diets are optimized, we look at how the environmental impact changes as the amount of the food increases.

If the impact goes up, the food has a negative balance; if it goes down, the balance is positive; if it stays roughly the same, the balance is neutral.

Why context matters: three food examples

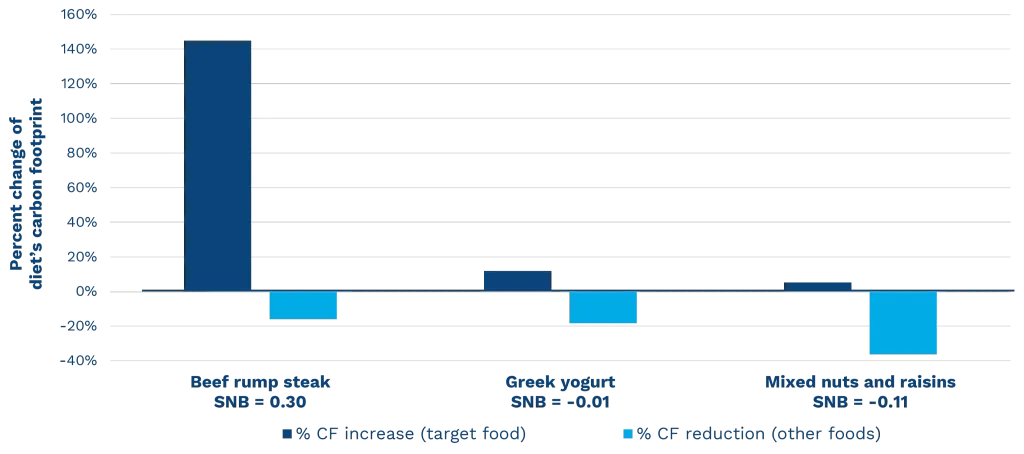

Figure 2 zooms in on three specific products to show how the SNB score works in practice:

-

Beef

-

Greek yogurt

-

Mixed nuts and raisins

Each example separates:

-

the direct carbon footprint of adding the product to the diet, and

-

the reduction in carbon footprint from foods that are displaced elsewhere in the diet.

For beef, the increase in carbon footprint from the product itself is only partly offset by reductions in other foods, leading to a strong net increase. For mixed nuts and raisins, the opposite happens: the foods they replace have a higher carbon footprint, resulting in a net reduction. Greek yogurt sits in between, with substitutions that largely offset its own carbon footprint.

These examples make clear that the net impact of a food depends on what it replaces/displaces to maintain nutritional adequacy, not just on its own environmental profile.

What this means in practice

This study shows that diet-aware tools like the SNB score can offer valuable new insights, but they need to be used with care.

The score compares foods within an optimized, nutritionally adequate diet, not within today’s eating habits. That means it helps explore what could work in a theoretical optimal setting, rather than describing the real-world impact of foods as people eat them now. Results also depend strongly on the quality of nutrition and environmental data, and a single score can be hard to explain without clear context.

Stakeholders agreed that looking at foods within whole diets is a big step forward, but warned that combined scores can easily be misunderstood, especially if used as simple labels or rankings.

For now, the SNB score is best seen as an exploratory tool to support discussion and decision-making, not a standalone or consumer-facing metric. With further development, this diet-aware approach offers clear potential to be explored in future consultancy. It can help companies better understand trade-offs and make more informed choices around sustainable food development.

Read the full scientific paper

Sustainability nutrition balance: A proof-of-concept metric integrating nutrition and environmental sustainability of foods in the context of whole diets

Alessandra Grasso, Marcelo Tyszler, Hans Blonk, Judith Groen, Roline Broekema, Thom Huppertz, Stephan Peters

Published in Cleaner Food Systems, 29 January 2026

Acknowledgement

We want to thank the Dutch Dairy Association (Nederlandse Zuivel Organisatie) for funding this research.

More information

Get in touch

Alessandra Grasso

Do you have questions about the Sustainable Nutrition Balance Score or are you interested in learning more about sustainable diets? Get in touch with Alessandra.