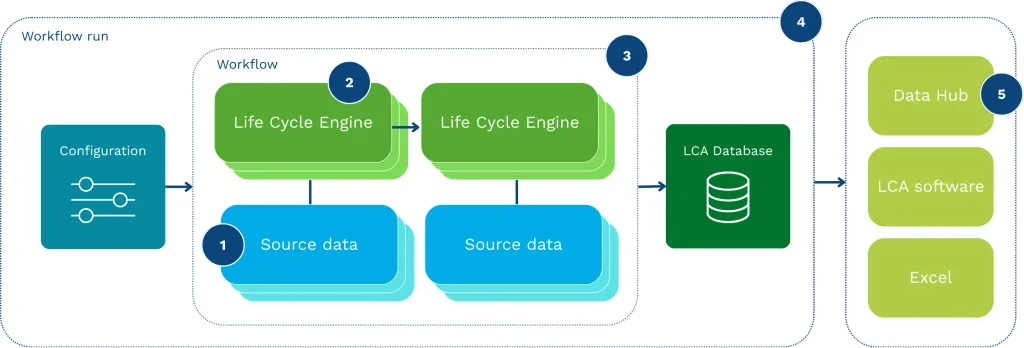

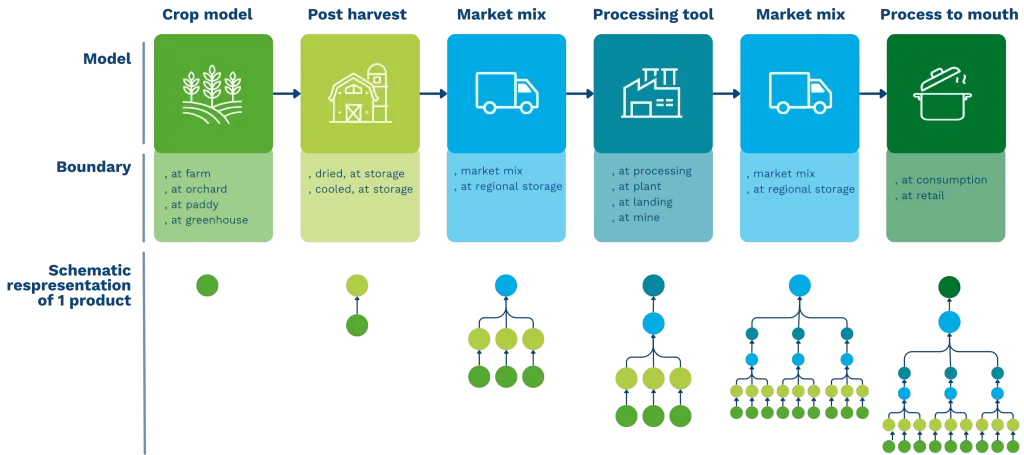

By encoding methodology into executable engines, the DGP transforms LCA from manual work into an automated system. This ensures that datasets are generated with consistency across the entire database, moving away from fragmented interpretations. Because every assumption is structured and fully inspectable, the logic behind the data is no longer hidden but transparent.

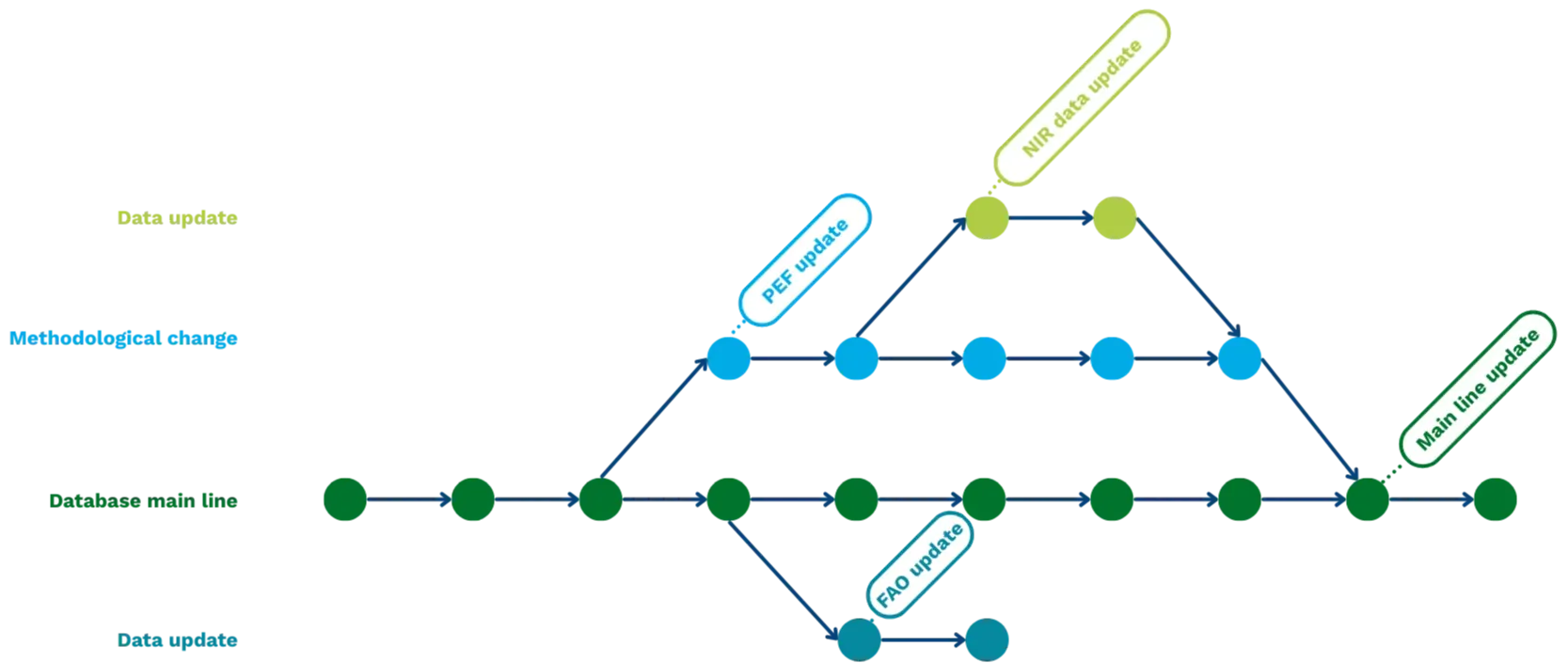

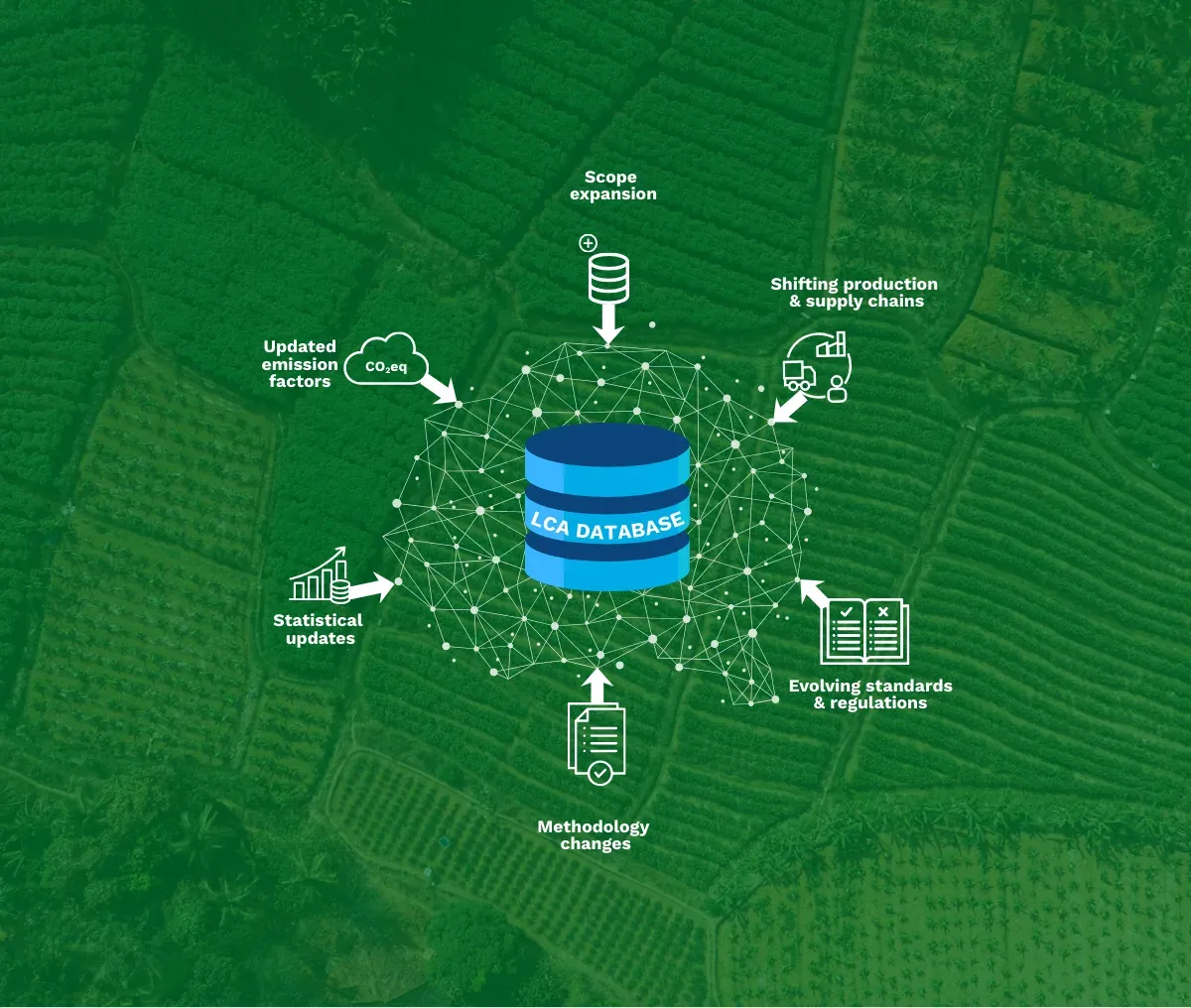

One of the strongest capabilities of Life Cycle Engines is how they support change. In practice, large LCA databases contain tens of thousands of datasets and hundreds of thousands (sometimes millions) of exchanges. At this scale, every change or update can ripple across a large part of the database. Examples of updates are new emissions factors, change in allocation method, or a correction in a shared data source.

In (semi) manual systems, these updates often get applied inconsistently. Some datasets are updated, others remain unchanged, and assumptions drift.

The DGP safeguards that cross-cutting corrections can be implemented at the level where they belong, such as in source data, in modelling rules (engines), or in workflow configurations. This results in a database that is regenerated in a controlled run.

Furthermore, this approach guarantees that every calculation step is reproducible, allowing updates to be propagated across the system instantly. For example, an engine variant could comply with a specific national inventory methodology or a defined program rule, while keeping the overall database coherent. This provides a structured way to support policy-driven or regional methodological requirements without fragmenting the database.