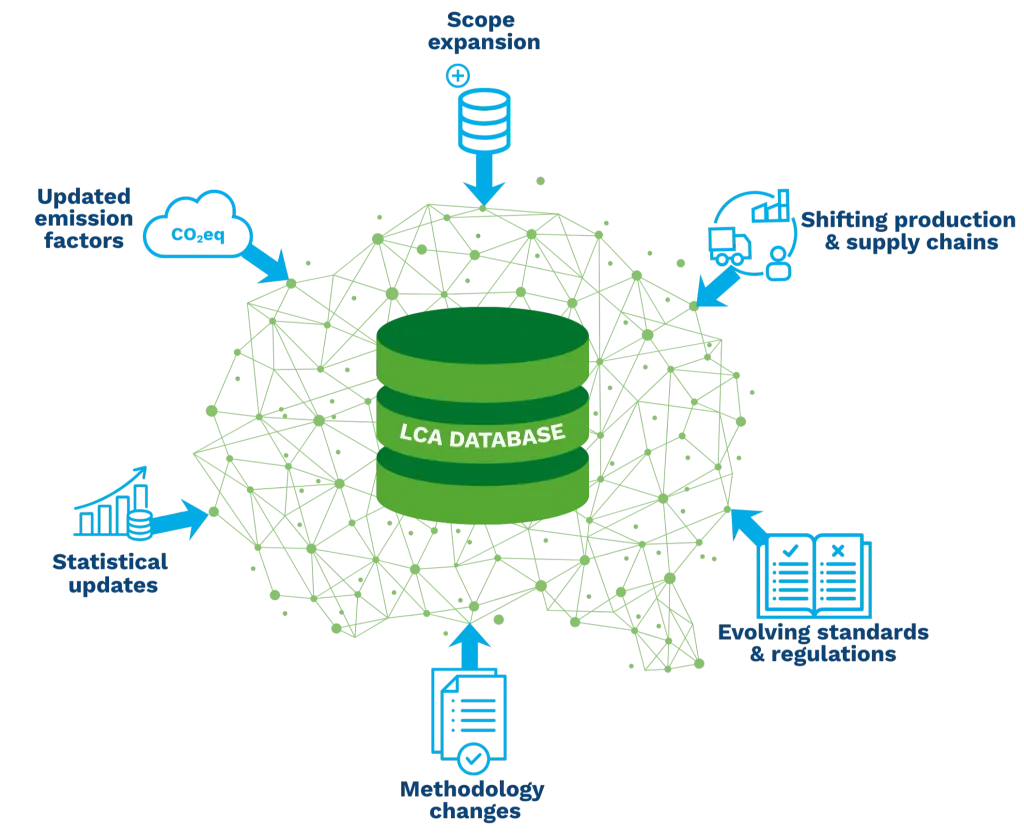

Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) and Carbon Footprinting have evolved from scientific tools into foundational methods for sustainability strategy, investment decisions, and regulatory compliance. Yet while the real world is dynamic, with shifting production systems, evolving agricultural practices, and changing emission factors and standards, many LCA databases remain static.

Where databases once mainly supported academic research, today they underpin corporate footprints, product declarations, policy scenarios, decarbonization roadmaps, digital product passports, and automated reporting. This has pushed LCA data into a new role: regulatory decision infrastructure.

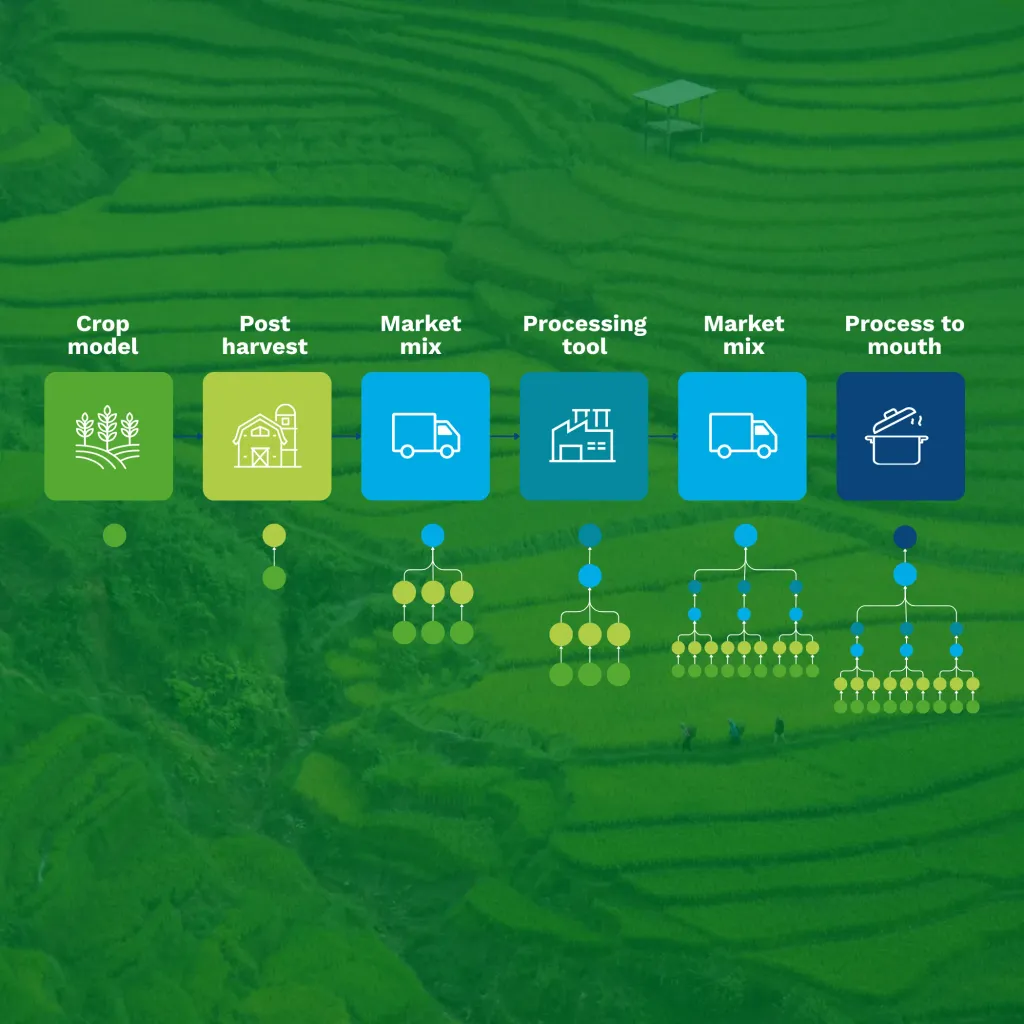

In a series of articles, we explore these challenges and introduce the Data Generation Pipeline, a system designed to create and maintain large-scale, future-proof LCA databases.